By Ben Paul

Professor Alan Willner is very accomplished.

He has been recognized by the US National Academy of Engineering, the UK Royal Academy of Engineering, the White House, the Guggenheim Foundation, the IEEE, and so on and so on.

He’s served as President of the Optical Society and President of the IEEE Photonics Society. He’s been the chair of several professional committees with long and important sounding acronyms. He’s served as editor-in-chief of no less than three scientific journals. He has produced over 350 refereed journal papers, 30 patents, and one book.

Now let’s talk about his real accomplishments.

There is a word in Hebrew, kehillah, which defined loosely, means a community. More than that however, akehillah is a group of people with a shared purpose or mission. It is a word that Alan Willner, an Orthodox Jew and leading engineer in the field of photonics, takes extremely seriously.

When I first knocked on his door at the Ming Hsieh Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering to speak to him about the work he is doing, it quickly became clear that Dr. Willner only wanted to talk about the community he is a part of at USC. It turns out that all the background reading I had done into twisted data-carrying electromagnetic beams had been for nothing.

In 1990, when Alan first walked in the door for an interview with then-chair Jerry Mendel, he was, as always, wearing a yarmulke (i.e., Jewish skullcap). Mendel immediately noticed and rushed to change the post-interview dinner reservation to a Kosher restaurant, which also happened to be owned by Steven Spielberg’s mother. “Of all the places I interviewed with, USC was the only place that accommodated my religious observance so sensitively and proactively,” Willner said.

A few months later, while walking along Venice beach on a beautiful January day with his fiancé, Alan decided to join USC Viterbi.

“From day minus one, I felt I was joining a real community, not just a workplace,” Alan said, referring to the day he was hired as an assistant professor.

But a most telling example of community Alan experienced in his early years had to do with an engineering department’s most valuable resource – lab space.

“After 6 months, I outgrew the space I started out in,” Alan said. “One day Lloyd Welch – a much more senior and well-known professor – came up to me and said ‘why not take my lab, you seem to need it more than me.’ This is simply something that doesn’t happen at universities!” Alan says, still surprised to this day.

That space soon filled up as well and another giant of the department, Irving Reed, offered him some room next door. “I was like the creeping goo,” Alan says proudly, “eventually I took over the whole wing and I never had to ask for any of it.”

|

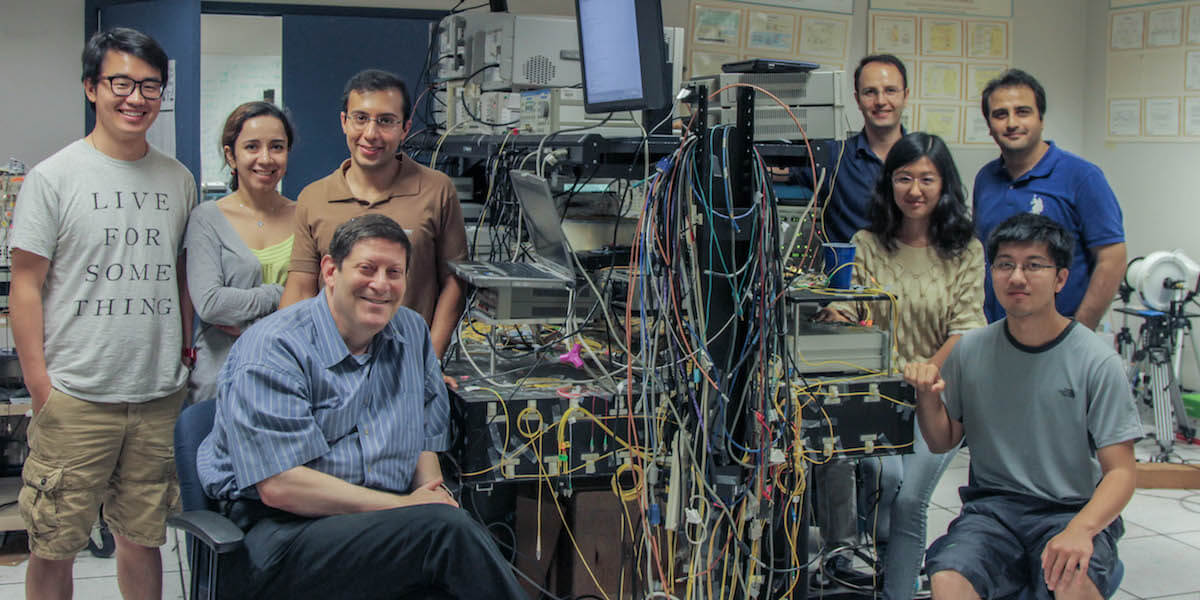

Alan Willner with students. Optical Communications Lab – Ming Hsieh Dept. of Electrical Engineering

|

Today, Alan is the Steve and Kathryn Sample Chair holder, honoring the late great USC President. His lab, the Optical Communications Laboratory, features 2,500 square feet of space. Here, he and his 14 PhD students use state of the art technology to conduct high-speed experiments on optical systems and devices.

His current students hail from six countries: China, Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the US. Throw in former students from Germany, India, Israel, Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey and suddenly that 2500 square foot lab doesn’t seem quite large enough to contain the grievances their nations could claim against each other.

“One important lesson I learned over the past 25 years is that USC does not just tolerate diversity, we celebrate it.” Alan says. “Just as my differences were embraced by the larger USC community when I first began here, I try to live by that standard with my students today.”

Twenty years ago, University of Minnesota Professor Imran Hayee was a PhD student in Alan’s lab. “Being a Muslim, I used to go to Friday prayers every week. He always respected that and made sure to arrange group meetings around my schedule,” Hayee said. “First, I was the only Muslim in the group, but since then several other Muslim students have joined.”

To this day, the group never holds research meetings on Fridays between 1 and 2pm in case any of the students want to go to Mosque. And Alan’s whole group has attended each of his four sons’ Bar Mitzvah ceremonies, even dancing together at the last one.

Alan and his students rarely talk politics, but they do discuss religion and culture — a lot. As the first identifiable Jew many of them have ever met, Alan encourages his students to ask him anything about his religion.

“My Chinese students tend to ask about kosher food – what it is and what it means.” Willner explains, as a large unopened jar of gefilte fish sits casually on his desk. “I once had a Muslim student ask me if Jews believe in the Devil. We don’t, and as it happens neither do Muslims. We ended up having a wonderful hour-long discussion about it in my office.”

“Before I joined the group I knew almost nothing about Islam or Judaism”, says 5th year PhD student Yongxiong Ren. “But I soon learned that they each follow lunar calendars, just like we Chinese do, with similarly deep meanings. This really strengthened the idea in my mind about respecting people with different backgrounds.”

Nisar Ahmed, one of Dr. Willner’s recent graduates from Pakistan, recounts what it was like to be in the lab. “Professor Willner’s lab had students from all over the world, including one student from Israel, which was particularly interesting to me because I had never met anyone from that country,” he said. “The two of us became close and while working together I was able to correlate many common beliefs between our faiths. He even invited my family to his home for Shabbat (Sabbath) dinner, an experience I may otherwise never have had.”

Dr. Willner’s new students are exposed to this environment the moment they first step into his lab. “When I joined, I was extremely nervous because I’d never had experience working with international students,” said Ahmad Fallahpour, a first year PhD student from Iran. “When I arrived, I found people from different nationalities, cultures, religions and educational backgrounds working together. Now I have mentors from China, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. I enjoy working with them because I get to learn about their cultures.”

Everyone in the group is acutely aware of their differences, but it is always approached in good humor. Willner recounts an episode when two students, a religious Muslim and a religious Jew (two good friends, both with long beards), were sitting next to each other in a research meeting.

The Muslim student reported that his experiment was working and the Jewish student reported that his was not. Willner turned to the Jewish student and said, “Look, he prays five times a day and you only pray three times a day. Of course his experiment is going to work before yours.” The entire group broke out in laughter.

So, to summarize: Alan Willner runs a lab full of students thrown together from a list of countries that collectively mistrust each other at best, and downright hate each other at worst. It’s like some sort of nerdy, engineering version of The Breakfast Club…with lasers.

The reality is that Alan’s lab actually thrives on this diversity. “Students aren’t homogeneous,” Alan says, “There may be rich differences in the way they approach work that stem from their background.”

|

Former Students Asher and Nisar

|

Some countries might tend to emphasize a broader approach to engineering, while others may educate students in more focused areas. One cultural institution might be more hierarchical, encouraging students to defer to older peers. Another might emphasize a more individualistic perspective. None of these facts define an entire culture or person, and neither are any of them more right or wrong.

“I try to take all the cultural aspects from my group and see how we can make them work together. What we end up with is a collection of best practices from all over the world that allows us to work really smartly and efficiently,” says Willner.

Yongxiong Ren has taken this idea to heart. “Among all the lessons I learned in our lab, the most important one is that diverse teams are smarter and more creative. Some exciting ideas and solutions to technical challenges come from our discussions and debates. This is thanks to our different backgrounds and philosophies.”

This is an approach to people and life in general that has implications outside of a basement laboratory. A few years ago, when Alan hosted a brainstorming session with U.S. Military DARPA Fellows, his students from the Chinese and Muslim world were able to interact face-to-face with uniformed military personnel.

“When the event was over, the military folks came up to me and told me how much it opened their eyes to be able to interact with people they don’t normally cross paths with,” Alan says proudly.

That’s not to say that just putting U.S. military officials and Iranian PhD students in a room together is going to solve any major geopolitical problems – but it couldn’t hurt.

“One of the greatest lessons I learned in Dr. Willner’s lab was about the cooperation between people from diverse backgrounds working together for a common goal with mutual respect for each other.” Nisar says. “Imagine how this mindset can change our world.”

This was quickly learned by Ahmad as well. “At first I was astonished that the group worked together so well. I soon realized that we all share the universal language of science, which unites people no matter where they’re from.”

Alan understands that these experiences not only make for better engineers, but for better people as well. And at the end of the day, that is what he’s really after. “Do my students come out as better researchers than when they started? I believe so. But are they also changed for the better? Are they happier? I certainly hope so.” He says as our interview concludes.

Somehow, an underground photonics lab in the electrical engineering department seems to be the perfect place for people and ideas to come together. These students are here because of their shared passion for engineering. They have a shared mission; they are a kehillah. Sure, they have political positions, and religious affiliations, and long memories, just like everyone else. But sometimes the best way to get people to understand each other is to put them in a lab and force them to solve the problem of optical-fiber-induced data signal impairments, together.

|

Photo courtesy of USC Viterbi |

Published on August 12th, 2016

Last updated on January 10th, 2019